Environmental misinformation spreads because it exploits complexity, uncertainty, and public anxiety about climate, health, and the future of food and energy.

It takes fragments of real data, removes context, and repackages them into claims that sound scientific but collapse under scrutiny.

Why Environmental Misinformation Accelerates Faster Than Other Topics

Environmental issues sit at the intersection of science, politics, economics, and daily life. That combination makes them uniquely vulnerable to distortion. Climate change alone involves atmospheric physics, long-term datasets, probabilistic modeling, and policy tradeoffs. This complexity creates space for misleading simplifications.

According to a 2023 analysis by the Reuters Institute, climate-related false or misleading content spreads more rapidly on social platforms than corrections or peer-reviewed explanations, largely because emotionally framed claims outperform technical accuracy in engagement metrics.

The problem is amplified by platform algorithms that reward outrage, novelty, and certainty. Claims that say “scientists are hiding this” or “this single graph proves everything are a lie.” They travel further than nuanced explanations that acknowledge margins of error.

Researchers from MIT found in a large-scale study of Twitter data that false information spreads significantly faster than truthful information, and this effect holds even when bots are removed from the dataset. Environmental misinformation benefits disproportionately from this dynamic because it often frames itself as “forbidden knowledge.”

The Difference Between Scientific Uncertainty and Manufactured Doubt

A central tactic in environmental misinformation is the deliberate misuse of uncertainty. Legitimate science always includes uncertainty ranges, confidence intervals, and revisions as data improves. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, for example, explicitly quantifies confidence levels using calibrated language such as “very likely” or “high confidence.” These phrases do not signal weakness. They signal transparency.

Manufactured doubt takes those uncertainty statements and reframes them as proof that nothing is known. A common example is the claim that because climate models differ slightly in projections, climate change itself is unproven.

In reality, model variation exists within a narrow band that overwhelmingly agrees on direction and magnitude. By 2021, the IPCC reported with over 99 percent confidence that human activity is the dominant cause of observed warming since the mid-20th century.

The table below illustrates how real uncertainty differs from misinformation-driven doubt.

| Aspect | Scientific uncertainty | Manufactured doubt |

| Purpose | Quantify limits of knowledge | Undermine consensus |

| Language | Probabilities and confidence levels | Absolutes and dismissals |

| Data use | Full datasets with methods disclosed | Selective or isolated data points |

| Revision | Updated as evidence improves | Claims “science keeps changing” to discredit |

Cherry-picking Data and The Illusion of Contradiction

Another hallmark of environmental misinformation is cherry-picking. This involves selecting a narrow slice of data that appears to contradict broader trends. A frequent example is citing a single cold winter or regional cooling trend as evidence against global warming.

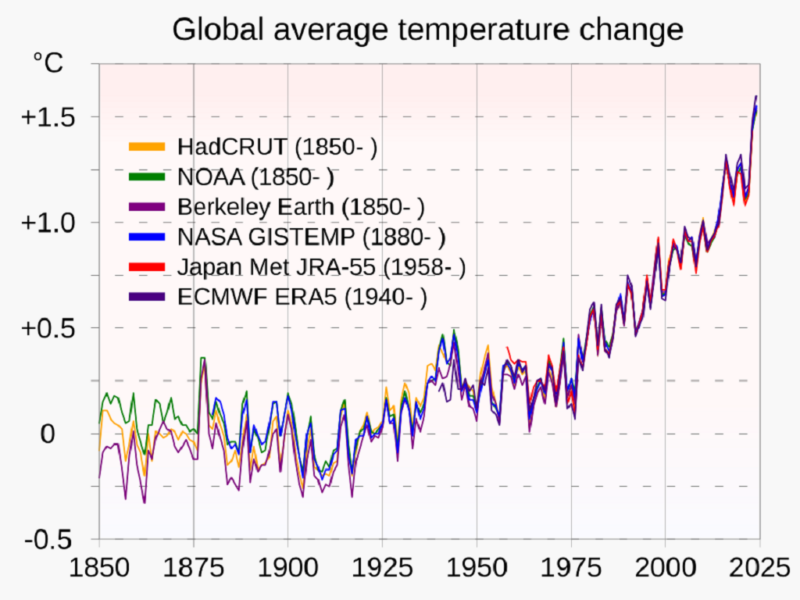

Climate science evaluates global averages over decades, not short-term regional variability. NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration both publish temperature datasets showing that while year-to-year variation exists, the long-term upward trend is unmistakable.

Cherry-picking also appears in biodiversity debates. Claims that species extinction is exaggerated often rely on localized recovery stories while ignoring global assessments.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List evaluates over 150,000 species using standardized criteria. Local population rebounds do not negate the documented increase in extinction risk worldwide.

Fake Experts and Credential Laundering

Environmental misinformation often relies on individuals presented as experts without relevant credentials or with affiliations that create conflicts of interest. A geologist commenting outside climate science or an engineer speaking on epidemiology may hold advanced degrees but lack subject-matter expertise. More subtle cases involve “credential laundering,” where titles are emphasized while funding sources or institutional ties are omitted.

Investigations by the Union of Concerned Scientists have documented repeated cases where fossil fuel–funded organizations promoted spokespeople as independent experts despite clear financial incentives. Legitimate scientific bodies disclose funding sources, publish methods, and submit findings to peer review. Misinformation sources rarely do.

The table below summarizes the differences between credible expertise and misleading authority.

| Feature | Credible expert | Misleading authority |

| Field relevance | Directly aligned with the topic | Tangential or unrelated |

| Publication record | Peer-reviewed journals | Blogs or opinion pieces |

| Funding transparency | Disclosed and documented | Omitted or obscured |

| Institutional accountability | Subject to review | Self-appointed or opaque |

Misuse of Graphs, Charts, and Visual Data

Visual misinformation is particularly effective because it bypasses critical reading. Environmental misinformation frequently uses truncated axes, inconsistent baselines, or misleading color scales to exaggerate or minimize trends.

For example, a temperature graph starting in an unusually warm year can falsely suggest cooling. This tactic is well-documented in climate disinformation campaigns analyzed by researchers at the University of Oxford.

Legitimate scientific graphics include labeled axes, time ranges, and data sources. They often show uncertainty bands rather than single lines. When a visual lacks context or sourcing, it should be treated with skepticism.

Another emerging layer of environmental misinformation comes from AI-generated content that mimics scientific language without being grounded in real data. Large language models can now produce convincing graphs, summaries, and even fabricated study abstracts that appear legitimate at first glance. In several 2024 media investigations, journalists found climate denial articles generated entirely by AI systems, complete with invented citations and non-existent journals. This makes surface-level credibility checks insufficient.

Tools such as an AI detector can help identify whether a text was likely machine-generated, which is increasingly relevant when environmental claims circulate without clear authorship, institutional backing, or traceable research trails. While detection tools are not definitive proof of misinformation, they add a verification layer when combined with source validation and data cross-checking.

Conspiracy Framing and the Collapse of Falsifiability

A defining feature of environmental misinformation is conspiracy framing. Claims that governments, scientists, and international organizations are coordinating to deceive the public are unfalsifiable by design. Any contradictory evidence is reinterpreted as part of the conspiracy. This structure removes the possibility of correction.

Studies in political psychology show that conspiracy-based narratives resist evidence because they provide emotional coherence rather than factual accuracy. In environmental contexts, this often appears as claims that climate change is a hoax to control populations or enrich elites. No credible evidence supports these assertions, and they directly contradict the diversity of independent research institutions involved in environmental science across dozens of countries.

How Peer Review and Consensus Actually Work

One of the most persistent myths is that environmental consensus is manufactured through groupthink. In reality, consensus emerges after decades of independent research, replication, and debate.

The IPCC does not conduct original research. It synthesizes thousands of peer-reviewed studies published by scientists worldwide. Authors and reviewers come from different political systems, economic interests, and academic traditions.

Peer review is not a guarantee of truth, but it is a filter against obvious errors, undisclosed conflicts, and unsupported claims. When misinformation sources dismiss peer review entirely, they remove the primary quality control mechanism of science.

Case Study: Climate Change Misinformation Versus Evidence

The table below contrasts common misinformation claims with established evidence.

| Claim | What evidence shows |

| The climate has always changed naturally | True, but the current warming rate and cause are unprecedented in the instrumental record |

| CO₂ is only a trace gas | Trace concentration does not limit radiative impact |

| Scientists are divided | Over 97 percent agreement in multiple meta-analyses |

| Models are unreliable | Models accurately predicted long-term warming trends since the 1980s |

Why Correction Alone is Not Enough

Research published in Nature Climate Change shows that fact-checking improves knowledge but does not always reduce belief in misinformation. Once false narratives align with identity or ideology, they become resistant to correction. This is why spotting misinformation early matters more than debunking it later.

In my own reporting experience, I have seen how quickly environmental myths become entrenched once they circulate within closed online communities. By the time corrections appear, the narrative has already shifted to distrust the source of the correction itself.

What Consistently Signals Credibility

Reliable environmental information shares several characteristics. It references primary data, acknowledges uncertainty without exaggerating it, and avoids absolute claims. It distinguishes between correlation and causation. It is produced by institutions with reputational risk and accountability, such as national academies, universities, and international scientific bodies.

Misinformation, by contrast, relies on certainty, selective evidence, emotional framing, and attacks on institutions rather than engagement with data. These patterns repeat across climate, pollution, biodiversity, and energy debates.

Conclusion

Environmental misinformation spreads quickly because it is designed to. It exploits complexity, distrust, and emotional response while avoiding accountability. Spotting it does not require specialized training, but it does require attention to how claims are made, not just what they assert.

Understanding the mechanics of scientific evidence, consensus formation, and common distortion tactics provides a reliable filter. In an information environment where speed often outruns accuracy, that filter is no longer optional.